Gotta Dance! The Power of Movement and Chaos in 1941

In wartime farce 1941, one of Spielberg's primary targets is masculinity, and in the film’s musical sequence, he finds the perfect platform to skewer it.

1941 sank like a runaway Ferris wheel when it hit cinemas in 1979. A wartime farce released after the triumphs of Jaws (1975) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), it was Steven Spielberg’s first major misfire, running over-schedule and over-budget during production and – crucially – failing with critics, many of whom didn’t see to the funny side of its wacky humour. The film’s problems seemed to become apparent to Spielberg during post-production when he spoke to journalist Chris Hodenfield in an interview for Rolling Stone. Noting Spielberg’s “grim countenance,” Hodenfield’s portrait is a surprisingly candid one in which Spielberg seems like a desperate man trying to put things right.

“I can’t correct the overall conceptual disasters in 1941, but I can get little pieces here and there that I think will help speed the pace. If you can’t do anything about it, then you’re at the mercy of what comics call ‘the death silence’. You expected a laugh and all there is is a hole.”

Steven Spielberg speaking to Chris Hodenfield, Rolling Stone, 1980

Even after the dust had settled and 1941 had made a respectable box office sum of just under $95m (well above its budget, but far below the more than $300m that Close Encounters took), Spielberg still seemed haunted. The productions of Jaws, Close Encounters and 1941 had gathered as many column inches as the films themselves, and the attention weighed heavy. He wanted to “make some amends for going way over on [those films]” and prove that he could “make a movie responsibly for a relatively medium budget that would appear to be something more expensive.” His next movie, Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), gave him the chance to do that and helped him recover from this minor blip. The rest, of course, is history.

With 1941, the wunderkind hero of New Hollywood had been taught a harsh lesson about letting one’s imagination run away with you. It was an appropriate lesson too because, beneath the zany surface, the film explores the tension between the order of the army and the chaos of war. This is a film of anarchic air-force pilots and stern generals who weep while watching Dumbo (1941); of sex-starved pilots using their planes to seduce horny old flames; of quaint little families whose home becomes the site for anti-aircraft guns. Looney Tunes legend Chuck Jones was hired to act as a creative consultant, and it’s to his work rather than any of Spielberg’s subsequent Second World War movies (or indeed any of Spielberg’s subsequent movies full-stop) that the most accurate comparison can be found. 1941 is a live-action Looney Tunes cartoon; it approaches authority like Bugs Bunny smacking a giant lipstick kiss on Elmer Fudd’s head.

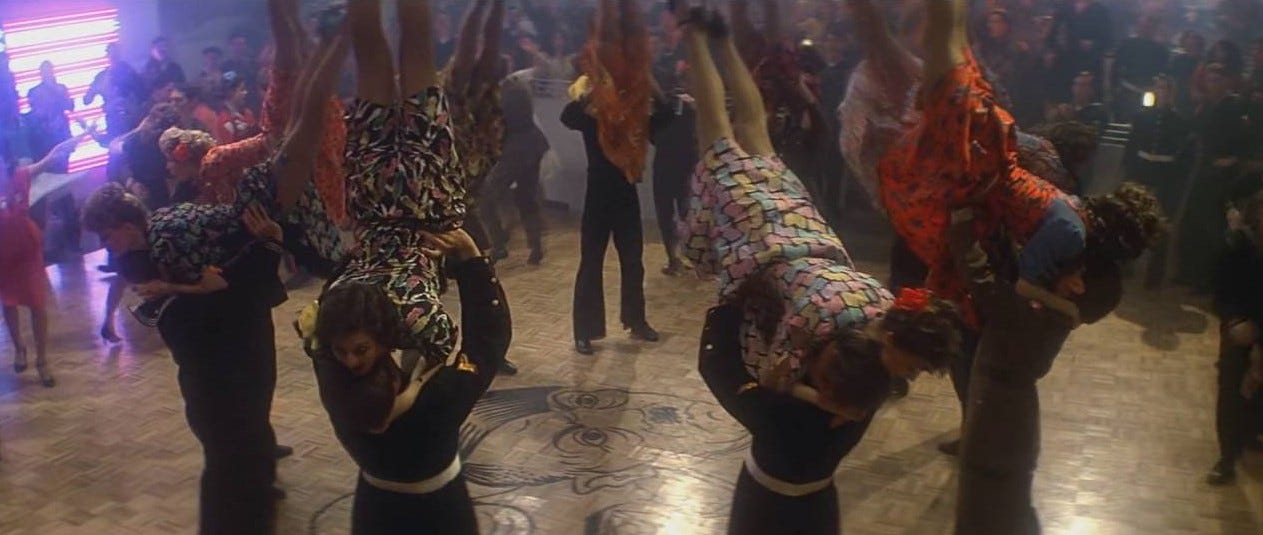

While this doesn’t necessarily mean the film is good (even after its modern reclamation as a lost cult classic, it remains largely unfunny and overlong), it does mean that there’s interesting work to be found. Chief among the gems is a grandstanding dance contest in which Spielberg indulges his love of musicals for the first time in his career. A swinging sequence that (in true 1941 fashion) throws everything at the screen, it features glorious choreography, sweeping camerawork and even a parody of Vincente Minelli’s 1953 masterpiece The Band Wagon. It’s the film’s undoubted highlight, and one that deserves closer attention for its overarching theme and use of two key traits of Spielberg’s filmmaking.

The first is his depiction of men. Among 1941‘s cacophony of characters are two young lovers: humble dishwasher Wally (Bobby Di Cicco) and his girlfriend Betty (Dianne Kay). Coming between them is Corporal Chuck ‘Stretch’ Sitarski (Treat Williams), a nasty bully who meets Wally at the cafe where he works and takes an instant dislike to him. Stretch intentionally trips Wally up while he’s doing his job and starts a fight that gets a film-long rivalry between the two off and running. Betty’s at the centre of this battle, with Wally learning to dance so he can partner with her at the forthcoming USO show, and Sitarski chasing her as a prize that he’ll win at any cost.

It’s a setup Spielberg has used since the very start of his career. In Duel (1971) he pits the gentle, somewhat cowardly David Mann against the hulking brute force of the truck, while in Jaws he doubles up, mirroring the mild-mannered Brody and Hooper with corrupt Mayor Vaughan and the alpha male Quint. These are binary visions of masculinity and you can see similar dynamics across many of his subsequent films: Rawlins and Basie in Empire of the Sun (1987), Schindler and Goethe in Schindler’s List (1993), Malcolm and Hammond in Jurassic Park (1993), Frank Abagnale and Carl Hanratty in Catch Me If You Can (2002), Lincoln and Thaddeus Stevens in Lincoln (2012) to name but a few. Though the meaning of these binaries has changed over time, they always speak to the role of power in the construction of masculinity.

The binary between Wally and Stretch is very much in line with those seen in Duel and Jaws: Wally is the Mann/Brody/Hooper of the film, while Stretch fills the role of the truck/Quint/Vaughan. The weak man and the strong man, the bullied and the bully. Like Mann and Brody, Wally does nothing to instigate or encourage the conflict (it just happens, like a force of nature), but again like Mann and Brody, he’s forced to step up and do something to stop it: he knocks Stretch out and proves his superiority. All three men become braver and stronger versions of themselves, without descending into the toxic masculinity that their enemies represent. In this early stage of his career, that’s the key goal of many Spielbergian heroes.

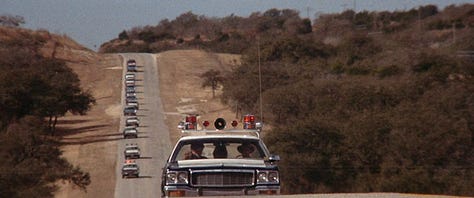

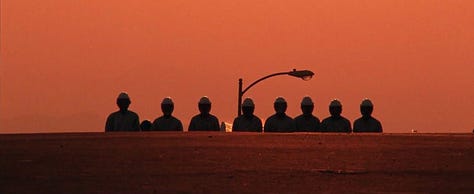

The second key Spielberg trait that’s relevant to 1941‘s dance sequence is his use of lines as representations of power and order. Take a look at the gallery below and you’ll see lines in each shot. Sometimes they run from the background of the shot to the foreground straight through the centre of the frame (for example, the shots of Quint and Lincoln), at other times they cut across the screen (E.T. The Extra-Terrestial (1982) and Bridge of Spies (2015)). While there’s often a darkness to the power and order Spielberg’s communicating (Raiders, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)), there’s also ambiguity; in some instances (Catch Me If You Can (2002) and The Post (2018), for example) Spielberg respectively asks us to question whether order is a good thing and whether the person who should have the power really does.

It’s no surprise then that 1941‘s dance scene is so striking. By positioning one of his alpha male bullies in a dancehall, Spielberg allows himself the opportunity to comment on masculine power in two ways; first by contrasting the elevated movement of a musical number with strict linearity and second by juxtaposing the masculinity of Stretch with an activity that’s traditionally defined as feminine. Rigidity and movement, order and chaos, fighting and dancing, alpha masculinity and fluid masculinity… they all come to a head in a sequence that ranks as one of the greatest Spielberg has ever put on screen.

The scene begins as it means to go on. We’re in a dance hall at a USO show and as the band strikes up, we see Betty being grabbed by the arm and dragged out by Stretch against her wishes. However, it doesn’t take long for the first of the sequence’s many reversals to arrive as she’s swiftly pulled back inside by Wally, who enters the club just at that moment. It’s an improbable and comedic switch that could easily have come from a Looney Tunes cartoon, a comparison that establishes the humour with which Spielberg will undercut Stretch’s sense of power.

His shot selection does the same. Spielberg captures this moment with a long-take tracking shot that follows Stretch as he leaves and Wally as he enters. It builds a sense of connection between the men but underlines their key differences: movement and pace. When Stretch leaves, he does so slowly and with fierce determination. The camera is at a distance, capturing him in a medium wide shot, as if it’s somehow scared to get too close. When Wally enters, however, he rushes in and the camera moves briskly along with him, Spielberg pushing in so the medium wide becomes a medium close-up of our young lovers locked together. Quickly, Spielberg has established static straight lines as the language of authority and rapid movement as the language of freedom. And there’s only one way to maintain that freedom. As Wally says: “we gotta dance!”

Realising that Betty’s disappeared, Stretch re-enters the dance hall slowly and purposefully. Spielberg’s camera is now in a medium close-up on him as he stares Wally down. Reacting, Wally spins Betty away to protect her and, in the same fluid movement, removes her jacket. He then uses it as a form of self-defence, covering Stretch’s face as he strides, in an arrow-like straight line, towards the couple. The fight (and dance) has now begun in earnest. Wally runs to his left, sliding along the floor to avoid the other dancers, and Stretch follows him, showing none of the same consideration by pushing others out of the way. He throws a punch, but Wally’s too fast and too nimble. He ducks Stretch’s fist, which flies into a wall.

This has all happened within one shot, which begins when Stretch walks towards Wally and Betty. The punch is the mid-section of the shot and from there, Spielberg’s camera lifts to capture the action as Wally runs into the club’s background and around the tables and chairs that occupy it. Stretch pursues him, of course, and the shot lasts for a total of 21 seconds before the next edit, which arrives when Wally vaults and Stretch bumps into a woman who’s being twirled around by her partner. This is a Road Runner cartoon in live action, and Spielberg catches Wally’s speed and agility with a shot that allows us to appreciate space and pace in real-time.

Once Stretch has recovered from his clattering, Spielberg resumes the scene with another straight line. Maxine (Wendie Jo Sperber), a plus-size woman and friend of Betty’s who harbours a crush on Stretch, slides towards the camera (across the dancefloor) and grabs onto Stretch’s leg. It’s a playful moment that riffs on Cyd Charisse’s iconic slide during the ‘Girl Hunt Ballet’ sequence in The Band Wagon (1953), but also another moment that hampers Stretch and associates him with all things linear and leaden. He’s almost literally chained to the ground.

When we cut back to Wally, he’s the exact opposite. Swinging Betty around among a crowd of revellers who are doing the same, he’s full of life and movement. Another cut and we return to Stretch as he seeks to resume battle. He walks over to his prey in the same way he entered the club: a straight line that cuts through other dancers. Wally once again outfoxes him though, lifting a woman who’s been turned upside down by her partner and handing her to Stretch. The woman is giggling and her legs are waving in the air as Stretch holds her. He turns direct to camera, dumbfounded, the woman’s crotch in his face. Stretch’s pursuit of ‘his’ woman has ended with him being humiliated by two ‘lesser’ women. Wile E. Coyote stands frustrated by yet another misfiring product from those fine folks at ACME.

It’s a humiliation that continues into the next part of the sequence, in which Spielberg returns to Maxine in order to further mock Stretch’s masculinity. Still eager to get a dance with the apple of her eye, Maxine barges through a group of people (not unlike Stretch) and runs across frame in a straight line (again, mimicking Stretch). She’s as dogged and resolute in her pursuit of him as he is in his pursuit of Betty and the parallels between them undermine him even more: not only is his wimpy rival getting the better of him, but women are dominating him too.

Adding to the embarrassment, Spielberg repeats his punchline from seconds ago. As Maxine rushes towards Stretch, Wally finds himself caught between them and uses his agility to crouch to the floor, lift his legs up and propel her directly into him. Again, Stretch is confronted with a woman’s crotch. Maxine flips him over and grabs him by the arm as he tries to escape. They’re essentially dancing, and Maxime bends Stretch over and plants a kiss on him in a reversal of the classic Hollywood trope.

Stretch finally escape and immediately returns his focus to his primary foe, throwing a punch that Wally avoids by leaping into the arms of the man standing next to him (another reversal of a movie trope, but one that empowers, rather than demeans, Wally). He runs around a table to avoid Stretch and its circular shape again underlines the core difference between the men and their movement. While Wally runs around the table and jumps on it to avoid capture, Stretch takes the more direct approach and yanks the tablecloth from under Wally’s feet in the hope he’ll slip off. Of course, he doesn’t. Stretch’s brute force and linearity are no match for Wally’s creativity and movement, and he simply backflips off the table leaving Stretch tangled in the cloth. Maxine has bested him by echoing his movement and Wally has bested him by representing its opposite. For all his might, Stretch is losing.

At this point, Spielberg changes the dynamic. Wally rejoins Betty and dances toward the camera in a straight line that cuts through the other dancers. Just like Maxine, Wally’s now mimicking Stretch’s movement, but doing so with style and grace. As the pair move off-screen, Spielberg then allows us to focus solely on the other dancers for the first time in the scene. They’re as bold and free in their movement as Wally, the men sliding their partners through their legs before hoisting them high into the air. They form a circle while doing this, reminding us of the circular table that foiled Stretch before and standing in opposition to Stretch’s typical linear movement. He’s now returned to the scene, waiting still and silently outside the circle. Wally and Betty are dancing wildly and Spielberg cuts to short shots of other dancers doing the same. Stretch, the epitome of order and conformity, is now the outsider.

Increasingly frustrated, he attempts to regain control of the sequence and Spielberg marks the moment with yet more linear composition. The camera picks Stretch up as he drags his hand down his face like a prizefighter steadying himself for the next round. He walks across the frame, pushing dancers out of his path, and looks around the screen for Wally and Betty, who true to form are dancing with glee. Stretch stops in his tracks and Wally does the same before calmly ushering Betty away. The two men are now facing each other, like gunmen in a Western. Rather than drawing pistols, however, Stretch simply attacks Wally and runs in a straight line towards him. Wally also runs straight, striding towards a wall, which he runs up so he can flip over Stretch. “Look at that!” the dance’s MC says in astonishment, and everybody does, turning in unison to watch Wally take centre stage… and, of course, disgrace Stretch.

The crowd is now utterly entranced in this fight-cum-dance. A row of sailors rushes towards camera and then another row cuts in front of them. A new shot follows another line of soldiers as they move forward, clapping and bopping along to the beat. A second row is already in place on the right of the frame to form a corridor that Wally and Betty are now at the head of, the whole shot built around them, our eye drawn towards them. Again, we have a straight line denoting power. Wally spins Betty and then vaults over her, sticking the landing perfectly. “That’s my best friend,” shouts one of Wally’s pals before adding reverentially, “and he’s dancing.” This isn’t a simple night out at a party. This is transcendental. Wally has learned the moves, found his rhythm and kicked off the shackles of his wimpy persona, turning the traditionally feminine act of dancing into a weapon that redefines the power of masculinity.

But it doesn’t last. Wally’s blissful movement is cut short in the most brutal way possible when Spielberg cuts to the next shot and shows us who’s at the other end of the corridor: Stretch. Stood in front of a neon American flag, he’s motionless except for ushering a handful of revellers from his line of sight. Unaware, Wally is spinning towards him, and so is Spielberg’s camera, as Stretch shakes his hands, clenches his fists and readies a punch. A quick cut back to the oblivious Wally and then another back to Stretch, who winds up and socks it straight at our hero. The force makes him stumble back up the corridor, before landing on his knees and sliding the rest of the way. It’s another callback to Cyd Charisse in The Band Wagon and another sign of Wally’s inherent fluidity. Even in defeat, he has style.

Yet, despite his knockout, Wally hasn’t lost entirely. If his tussle with Stretch is about movement versus stillness, chaos versus order, then the order Stretch creates doesn’t last long. Attempting to throw a chair at Stretch in revenge, Wally’s friend hits another soldier and a fight breaks out between the two of them. Soon enough, the whole dancehall is involved, soldiers squaring up to sailors in two straight lines. It’s perfect order until all hell breaks loose and a full-on brawl erupts.

Wally’s lost the battle but won the war. Movement – unstifled, unregimented, uninhibited movement – reigns supreme. And in this world of war run amok and armies torn asunder by paranoia, movement is perhaps the only victory worth earning. 1941 has no respect for anything: nation, war, masculinity are all roundly mocked. There’s only one rule here and it’s really simple: ya gotta dance!