The Man in the Machine: Science Fiction, Language and The Terminal

Steven Spielberg draws on the work of Frank Capra and Charlie Chaplin to tell a sci-fi tinged story of language’s triumph over mechanisation in his light comedy, The Terminal

The Terminal opens with the sights and sounds of a busy airport. Throngs of people move from one place to the next, stamps are pounded onto passports and letters flicker restlessly on departure boards. Every little detail is a cog in the airport’s wider machine, and each cog is precision-engineered to perform its assigned task. Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock. It goes around with the precision of a clock, never failing, never slowing down, never speeding up. Until, that is, something gets in the way. The machine develops a glitch, and the glitch is a man.

When The Terminal was released at cinemas in late 2004, it arrived with something of a thud. A whimsical romantic comedy, it was notably different to the popular films of that year (animation [The Incredibles, Shrek 2], fantasy [Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban] and superheroes [Spider-Man 2] dominated the box office, while Million Dollar Baby scooped the major awards) and stood in stark contrast to the sombre mood Spielberg himself seemed to be striking. Catch Me If You Can laced its candy-floss surface with a melancholy centre, while his two prior films and the one he released immediately after were dark science fiction offerings: A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), Minority Report (2002) and War of the Worlds (2005). Why, in the middle of this run, release something so utterly different, so seemingly inconsequential?

The answer is that The Terminal really isn’t all that different from the sci-fi trilogy that surrounds it. Yes, it’s certainly true that the film is a comedy and a very broad one at that: it’s sweet and sentimental and many of its laughs are drawn from Tom Hanks doing a funny accent. But it’s also true that there’s something much more serious and much darker than the feather-light exterior suggests. This is, after all, a film directed by a Jew who suffered anti-Semitic bullying as a child that’s about an immigrant being refused entry to a cold, inhumane United States.

A handful of critics picked up on these darker instincts at the time and noted connections to classic films and literature. Empire’s Ian Nathan, for example, called The Terminal a mix of Frank Capra and Franz Kafka, while others picked up on the connections to Jacques Tati’s 1967 film Playtime. There is, however, one influential film many critics missed, but which is just as – if not more – important in understanding The Terminal: Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936). Both are semi-science fiction. By this, I mean that while neither film features the visual trappings we traditionally associate with the genre (spaceships, aliens, laser beams) both lock into what remains its biggest thematic concern: the relationship between man and machine. For Chaplin, that machine was industrialisation and the greatest weapon against it the simple power of a smile; for Spielberg, it’s capitalism and the American Dream, and the battleground is language. In both cases, the consequence of obeying the machine is dehumanisation and the erosion of empathy.

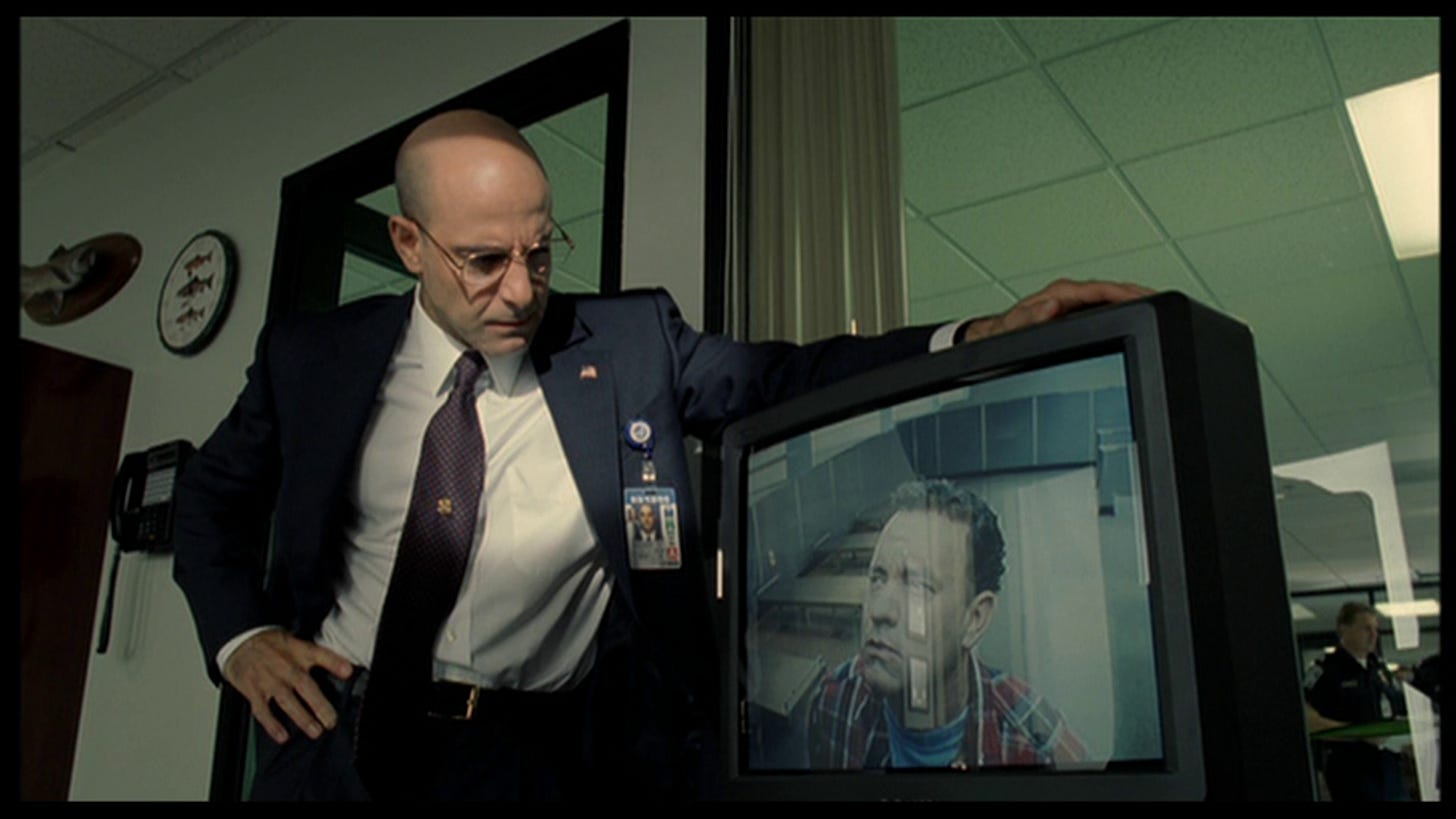

The machine in The Terminal is the airport itself and Spielberg establishes its dominance and effects on our two primary characters in the early moments. Above the cacophony of the opening scenes, airport chief Frank Dixon (Stanley Tucci) watches on. A bank of monitors is laid out before him and he uses them to survey everyone that enters the airport’s doors, including a group of tourists who he correctly identifies are travelling illegally. In amongst this, we’re introduced to our Little Tramp, Viktor Navorski (Tom Hanks). His passport is denied, and he’s subsequently ushered away from the check-in desks by airport officials, cordoned off and surrounded in blue ribbon. He is, as he’s later told, “unacceptable,” a spanner in the great bureaucratic machine that needs to be expelled.

Language is the tool through which this expulsion is attempted – and resisted. New to the country and unfamiliar with English, Viktor has no idea what’s going on or what anybody is saying. He’s brought to Dixon’s office and told that there’s been a coup in his country Krakozhia, but nothing sinks in; he simply corrects Dixon’s pronunciation and continues to act as if he’ll soon be on his way. There’s a certain rebellion to Viktor’s cluelessness. He can’t understand what’s being said, so even if Dixon were being precise and empathetic in his language, Viktor still wouldn’t understand. Of course, Dixon isn’t precise or empathetic. Throughout the film, screenwriters Jeff Nathanson and Sacha Gervasi give Dixon impenetrable jargon that he robotically parrots as if he’s reading from a manual.

“I have a bit of bad news. It seems like your country has suspended all travelling privileges on passports that have been issued by your government and our state department has revoked the visa that was going to allow you to enter the United States… All the flights in and out of your country have been closed indefinitely. And the new government has sealed all the borders, which means that your passport and visa are no longer valid. So currently you are a citizen of nowhere… You don’t qualify for asylum, refugee status, temporary protective status, humanitarian parole or non-immigration work, travel or diplomatic visas. You don’t qualify for any of these things.”

In the face of such jargon, it’s difficult to know who’s speaking the foreign language. Certainly, there’s only one person here who seems to be communicating, who seems human, and it’s the man who’s just been told he doesn’t qualify for any basic human rights. On the verge of a major promotion, Dixon has become so obsessed with upholding the system he’s responsible for that he’s unable to understand the world beyond its walls. He’s desperate to get Viktor out of the way and that means leaving him to fend for himself. Feigning empathy, he explains that he “has no choice but to allow [him] to enter the International Transit Lounge” where he’s “free to go anywhere [he likes]” as long as it’s “within the confines of the International Transit Lounge.” Space, movement and comfort are suggested by these three words, but Viktor has now had them taken away. It’s the dark, almost Orwellian erosion of meaningful language, and it underlines the dehumanising absurdity of this conveyor belt world. The machine must keep working, even if it needs contradictions to do so.

In a superb run of sequences, Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski then bring this world without communication to life visually. Viktor is ushered out of Dixon’s office into a corridor. Lit by brilliant white light and captured in silence except for the clip-clop of shoes on the floor, it’s as sterile and robotic as something from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). A key pass opens the door through to the airport itself with an electric buzz, and Viktor is finally at his destination. Again, it’s all shiny floors and clean white surfaces – a perfect miniature society running like a well-oiled machine – and Spielberg captures it with a dizzying long take that lasts 56 seconds and circles around Viktor as he struggles to take it all in. Finally composing himself, he asks what he’s supposed to do and gets a simple answer: “there’s only one thing you can do around here: shop.” For Dixon, people are a means to win promotion; for those in the terminal, they’re a means to make money. The conveyor belt keeps turning.

Now within the airport, Viktor hears the Krakozhia national anthem on TV and realises just how desperate his plight is. He runs to the set to watch a report about the revolution back home, but it quickly changes to another report. He looks for another TV and finds four of them, but they too change. A wide shot captures Viktor climbing the stairs, flanked on either side by escalators; already he’s a rat within a maze. He finds another screen, but the sound is down and when he asks people to turn the volume up, nobody pays attention. He tries to gain entry to a private lounge where the TV is on and the sound is up, but is refused entry, glass doors shutting and morphing him into something alien, somewhat like David in A.I.. All these TVs, all these people, all these chances for communication, but nothing can help Viktor. Like Chaplin struggling to keep up with the machine feeding him corn, technology is rampant here but language and communication is missing.

Another long take concludes the sequence. Lost and alone with nobody willing to help or even talk to him, Viktor stands stricken in the middle of the lounge. Spielberg begins on a close-up and slowly pulls out for 28 seconds to an extreme wide shot, going so far that Viktor can’t even be seen any more. He’s a ghost in the land of the living, a mute in a world of endless noise, and as lost in the teeth of this machine as the Little Tramp was in the cogs of his.

Ensuring that these teeth bite are the rules and regulations that govern the airport. They’re another form of the machine’s oppressive language, and they have an immediate impact on Viktor. With no home, no money and no rights, he’s left to dwell in the terminal and tries to survive as best he can by getting some sleep. Even this simple task is riddled with problems though: rows of seats are bolted together and their arms make lying down impossible – which is, of course, by design. However, Viktor won’t be beaten. Using a swiss army knife, he unscrews the arms and pulls the rows together to form a makeshift bed. The lights and incessant muzak remain a problem, but Viktor innovates again, finding the fuse box and pulling the plug. It’s a small victory for most, but in the context of his day, it’s a major triumph for Viktor.

Significantly, it’s also a lawful triumph. No matter what wrongs are visited upon him, Viktor never breaks the law; after all, he’s a communicator and this is his new home’s language. His trick with the seats can’t be considered vandalism because that area of the airport is undergoing construction anyway. Pulling the plug isn’t vandalism either; he can just plug it all back in come morning. Time and again he does this: making meals out of free condiments in the terminal’s food court and earning money from a machine that spews out a coin when a luggage cart is returned. He uses what’s around him to legally build a little life for himself and as the film progresses, he becomes a model citizen in this microcosmic society, a perfectly functioning line of code, rather than a glitch.

Knowing that any untoward action would compromise his promotion, Dixon also adheres to the law but while Viktor uses the language of the terminal to reach out, Dixon uses it to push back. He wants Viktor out and offers him access to New York, a proposal which – if accepted – will lead to his quick arrest and deportation. As the plan forms, Spielberg frames Dixon within a pane of glass. This allows Spielberg to play with his villain’s image, using reflection, light and markings on the glass to make him seems cold, broken, even robotic – a physical manifestation of the system he’s upholding. Again, we’re reminded of Spielberg’s depiction of David in A.I. and John Anderton in Minority Report. The unthinking automation of technology alienated those characters, here it’s the unthinking immorality of greed and ambition that alienates Dixon.

However, when the plan is put into action, it’s clear who has the last laugh. Knowing that he’s being conned, Viktor refuses to leave and instead shouts “I wait! I wait!” at a CCTV camera that Dixon’s been using to keep tabs on him. Spielberg captures the moment inside the airport’s command centre as Dixon and his team watch Viktor’s defiance on a bank of TV screens. His face dominates each one, repeated over and over again so that he’s all Dixon can see. Once more, Viktor has used the tools of the machine he finds himself in to undermine it. Dixon, meanwhile, has been thwarted and is now mocked through the very machinery he’s tried to manipulate.

As Viktor’s time in the airport goes on, he’s forced to adapt – most notably by learning English – but with limited resources at his disposal, he has to improvise. In one scene, he buys a Guide to New York book in both English and his native language so he can compare the words. In another, he keeps track of the ticker on the news channels, reading what words he can and committing them to memory. The nature of the words he learns is not coincidental: the book mentions the TV series Friends, the ticker addresses events in Krakozhia. Friends, family, the comforts of home. For Viktor, words are warmth; for the mechanics of the terminal, they’re anything but.

Having had his luggage cart income cut off by Dixon, Viktor tries to get a job, but the linguistic trappings of the micro-society again stifle him. Asked by one store owner if he’s local, he replies that he lives at Gate 67: an honest answer, but one that elicits laughter. When he goes to a watch store, he’s asked for a social security number and a drivers’ licence number, while the Discovery Channel store insists on a mailing address and telephone number. Of course, Viktor can provide none of these things. When not on the job hunt, he continues to apply for a legal way out of the airport, and continues to be denied. Officer Dolores Torres (Zoe Saldana) is sympathetic to Viktor’s plight, but bound by the demands of her job. In the terminal, the warmth of Viktor’s words are frozen stiff into code numbers, forms and stamps. Hard. Cold. Brutal in their efficiency. Language as a means of control, not communication or compassion.

It’s no surprise then that when Viktor does get a job it’s because he navigates around the red tape. Instead of applying for a job, he sees some manual labour that needs doing and simply does it: self-made work for a self-made man. Of course, it’s not long before another man seeks to un-make him. With an inspection of the airport looming and the now gainfully employed Viktor thriving, Dixon does the only thing he can: he locks Viktor up. “He has no nationality, no country, so automatically he’s a national security risk, according to my interpretation of section 2.12,” he tells his superior on the phone. “So all I’m asking for is that you put him in a federal detention centre and run a clearance on him.”

More jargon, more codes, more words used to oppress. It’s standard operating procedure for Dixon, and Spielberg once again uses technology to associate him with the cold process of machines. As Dixon justifies his actions, he stands by a TV monitor that’s playing footage from Viktor’s holding cell. As he did earlier in the film, Viktor stands close to the camera watching him. He’s imprisoned in technology, but Spielberg uses comedy to help him fight his way out. He glances to his right, so he’s looking directly at Dixon. It’s a silly and somewhat nonsensical moment (Viktor can’t know that Dixon’s standing in that position, so what’s he actually looking at?), but it connects to the sci-fi notions Spielberg is playing with. Dixon’s machine is looking back at him – and eventually, it bites him.

As the film continues, the pressure starts piling on Dixon. There’s an inspection of the airport and he needs everything to be perfect: his promotion rests on it. Things seem to be going pretty well as he guides the inspection team around the facilities and thwarts a drug dealer trying to smuggle cocaine concealed in walnuts. As he does this, he continues to talk in the cold and mechanical way that typifies his personality, telling the group that “we process about 600 planes a day with a processing time of 37 minutes per plane and about 60 seconds per passenger.” Viktor’s still locked up at this point, but soon necessity demands his release and produces an opportunity for him to embarrass Dixon yet again.

A Russian man has arrived at the airport with medicine for his sick father that’s banned in the US. The man begs, but Dixon is insistent: “in order to export medicines from this country he needs to have the proper form, he needs to have a medicinal purchase licence.” As usual, he shows no compassion, no humanity, just a dogged adherence to jargon and regulations. But Viktor – now out of his cell and acting as a translator – turns the tables. As the man is carried away, Viktor corrects himself, saying that he initially misunderstood the dialect and that the word for ‘father’ in his language is similar to the word for ‘goat’. Medicines for animals don’t fall under the same jurisdiction as those for humans, so this simple ‘misunderstanding’ means that the man can keep hold of the pills. As Dixon points out, Viktor’s been reading immigration forms and has used the rules of the system against it. It’s the only time Viktor comes close to breaking the law, but he does it for positive reasons: to help not hinder, to communicate, not control.

This act of rebellion finally causes Dixon’s mask to slip. Angry, he grabs Viktor, holding him over a photocopier (again, Dixon is associated with technology) and threatening him with deportation. Gone are the jargon and rules, replaced by a simpler kind of language, a language more akin to the kind of simplicity Viktor has displayed, but much more angry and violent. “You go to war with me and you go to war with the United States of America,” he tells Viktor. “And then you will know, when that fight is over, why the people of Krakozhia wait in line for cheap toilet paper while Uncle Sam wipes his ass with Charmin two-ply.” He’s spotted by his superiors and knows that his promotion is now at risk.

Viktor, on the other hand, becomes something of a folk hero. His moment of self-sacrifice and (most importantly for Spielberg) communication across the language barriers establishes him as an icon. The word is spread through the oral tradition. Workers gather round to hear stories of what happened, and while those stories are gross exaggerations, that’s part of the point. Words are power when used in the right way: to bridge gaps rather than build walls. This is underlined by the symbol of that triumph: a photocopy of Viktor’s hand, captured when Dixon had him by the throat. It’s a potent image: of rebellion, of friendship and of Spielberg’s career. Open hands reaching out were heavily featured in the marketing campaigns for E.T. and Schindler’s List, and here the photocopy becomes a poster of sorts for Viktor. It captures in a single image who he is and communicates an essential truth about the power of language.

With the film entering its last act, we finally see what Viktor’s efforts are in aid of: jazz autographs owned by his father. The collection features the signatures of each of the musicians featured in Art Kane’s iconic 1958 photograph ‘A Great Day in Harlem,’ except for one. Benny Golson is missing and Viktor has come to the United States to attend a Golson show, complete the set and pay his respects to his father. It’s another moment where Spielberg, Nathanson and Gervasi use language to underline the science fiction concepts The Terminal plays with. Viktor’s prize possession contrasts sharply with the tools of the terminal. Rather than video monitors, Viktor has tattered photographs. Rather than stamps, Viktor has handwritten notes. It’s a manual life versus an automated life and when Dixon returns to scupper Viktor’s plan once again (threatening to deport his friends if Viktor doesn’t do as he’s told), it’s telling that the film cuts to the departure board we saw in the opening titles. The letters spin, the words change. Dixon, the terminal, a machine-like life have won again – if only for a brief time.

Shortly after, one of Viktor’s friends, Gupta, an elderly Indian man who fled his home after assaulting a corrupt police officer, sacrifices himself by holding up the plane bound for Krakozhia on the runway. It’s a literal man versus machine moment and also a crime that leads to his arrest and certain deportation. But there’s method behind the madness. The flight is now delayed and Dixon’s threats are partially nullified, so Viktor makes a run for it. He heads to the terminal’s doors as Dixon furiously barks orders at his officers from the airport’s command centre. But times have changed. As Viktor heads towards the doors, Spielberg echoes the shots he used when Viktor first arrived, but instead of being alone, he’s now followed by the friends he’s made, all offering gifts and shouting sorry farewells. The stories about Viktor have broken the system’s mechanical spell because they represent language as connection and position communication over compliance.

The officers catch up but instead of stopping him, they let him go. Viktor is a free man, and as he heads out, Spielberg frames him within glass doors in an echo of those earlier shots of Dixon. He closes his eyes and breathes the cold air of a snowy city for the first time. The camera pulls out, as another reminder of Viktor’s arrival sequence (this time nodding to the 58 second long pull out), and while the traffic is gridlocked with taxis, Spielberg positions that as a good thing. At last, it’s life, movement… transit. Viktor has escaped the teeth of the terminal and can finally complete his task. He meets Benny Golson and, in an ironic twist, has to wait while the musician performs. But in sharp contrast to the wait he had in the airport, this one isn’t all bad. Capturing the film’s message, Spielberg and Kaminski bathe Golson in a heavenly orange glow, while a teary Viktor watches on. It’s another kind of language, one where notes replace letters and melodies replace sentences, but the beauty of communication and its power to move, rejuvenate and transform remain.

His task complete, Viktor hails a cab and is asked where he wants to go. “I am going home” he says before Spielberg cuts to his final shot: a warm, beautiful image of Times Square all lit up at night. It’s a sweet moment, but also a Spielbergian sucker punch. Like his three early Noughties sci-fis and so many of his post-2000 films, this happy finale masks a certain anxiety. The shot echoes those wide shots of the terminal and the message seems clear. New York, and the United States as a whole, were once home to “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” But in a mechanised world where communication stifles rather than strengthens connection, they’re certainly not home any more.