The Spielberg Hero

With the trailer for Indiana Jones 5 finally hitting the internet, let's take a quick look at the Man with the Hat and how he fits into Spielberg's roster of male heroes.

What is a typical Spielberg Hero? The answer seems pretty clear: an ordinary guy who finds himself in extraordinary circumstances. Think David Mann in Duel, Martin Brody in Jaws, or Alan Grant in Jurassic Park. All are prime examples of what Spielberg has called his ‘Mr. Everyday Regular Fella.’

But this tells only half the story. Dig deeper and many of Spielberg’s most significant heroes fit into one of a broader range of archetypes he’s returned to time and again. As Indiana Jones is set to return to cinemas next year (albeit under the direction of James Mangold), let’s start with him.

The Adventurer (Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones)

Indiana Jones is the closest Spielberg gets to a typical cinematic hero, but he’s certainly an unusual one, being morally ambiguous and sometimes ineffective. Indy either loses or destroys the MacGuffin every time and instead learns the value of respect: for higher powers in Raiders, for community in Temple of Doom, for his father in Last Crusade, and for knowledge in Crystal Skull.

Indeed, while the likes of Schwarzenegger and Stallones were establishing American superiority in many 80s Hollywood action films, Spielberg was interested in showing a character who was fundamentally human. Indy’s flawed and out of his depth, having to use his intellect — not just a weapon or pure strength — to negotiate his way out of danger. He’s a key Spielberg character because he never gets what he wants, but always finds what he needs: as Henry Snr puts it, “illumination”.

The Action Hero (Tom Cruise as John Anderton and Ray Ferrier)

In Minority Report and War of the Worlds, Spielberg plays against Tom Cruise’s action man screen persona to provide a powerful critique of it. Look, for example, at War of the Worlds. Cruise’s Ray Ferrier starts the film as a thoroughly loathsome person and an utterly unfit father. He slowly embraces his more paternal nature and ultimately reunites his family, but only after being forced into some morally dubious actions (including murder) along the way. At the film’s end, he remains physically apart from his ex-wife and kids, Spielberg showing that even blockbuster heroics can’t heal a broken home.

Minority Report takes the concept even further, not only undermining Cruise’s action-hero swagger but also physically mutating him. Spielberg has Anderton replace his eyeballs and painfully distort his face in order to evade capture, and even then, he still gets locked away. Like War of the Worlds, the film ends on a superficially happy note as Anderton and his wife are reunited and the Pre-Cogs are set free, but problems linger. Crime is now possible again and the fate of Anderton’s lost son is still a mystery. For Spielberg, the Cruise action hero doesn’t succeed, not totally. He simply survives.

The Everyman (Richard Dreyfuss as Matt Hooper, Roy Neary and Pete Sandich)

Dreyfuss is the young Spielberg’s cinematic avatar. The bullying Hooper faces at the hands of Quint in Jaws reflects the bullying Spielberg endured growing up, while the childish wonder Neary has in Close Encounters of the Third Kind reflects Spielberg’s own sense of awe. They’re funny, engaging everymen - the epitome of Spielberg’s ‘Mr. Everyday Regular Fella’ type - who are designed to elicit audience sympathy and provide relatable pathways into their films’ drama.

Always, however, is a little different. It’s a remake of one of Spielberg’s childhood favourites - 1943’s A Guy Named Joe - and stars Dreyfuss as Pete, a reckless aerial firefighter who’s killed on the job. By casting an elder Dreyfuss in a film he held dear as a child, Spielberg is subverting the Peter Pan image that had been constructed around him and calling into question the sanctity of his typical everyman. As Pete wanders into the afterlife at the film’s end, Spielberg leaves us with a message that’s surprisingly dark for an otherwise light film: mature or die.

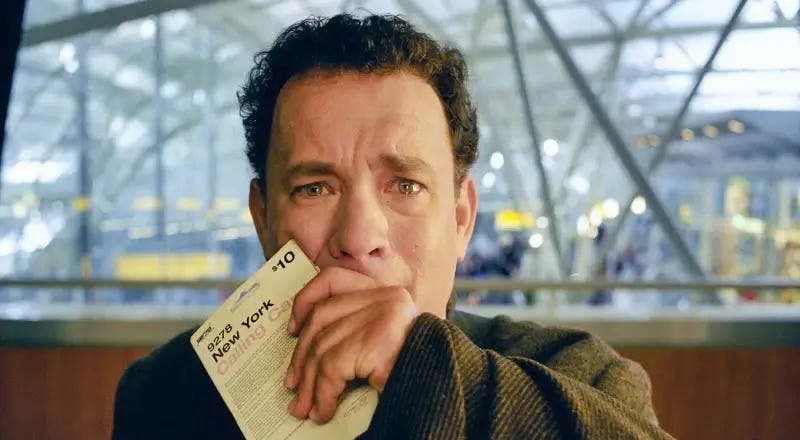

The American (Tom Hanks as Captain John Miller, James Donovan, Carl Handratty, Viktor Navorski and Ben Bradlee)

Hanks is Spielberg’s embodiment of America, his Jimmy Stewart, and he uses him to question American values. In Saving Private Ryan, Bridge of Spies, and The Post, Spielberg plays the Hanks characters straight but adds a touch of moral ambiguity. Miller’s life-and-death decisions, including leaving a young girl to languish in a battle-ravaged town, touch upon America’s late entry into the conflict, while Bridge of Spies and The Post show how Donovan and Bradlee have to risk breaking the law in order to uphold it.

If these films suggest that America is not as squeaky clean as it might hope, The Terminal trashes the belief entirely - albeit in the nicest way imaginable. A sweet romantic comedy, it casts the great American everyman as an immigrant abandoned in the titular airport. As Viktor makes a life for himself, he shows more grace, sincerity, hard work, and ambition than many of the Americans in the film. While he’s embraced the American Dream, they’ve abandoned it, and there’s a sense of bitter melancholy in the final shot of a wintery Times Square. Home may be a fractured country in the throes of revolution, but at least it’s better than modern America.

The Elder (Mark Rylance as Rudolf Abel, The BFG and James Halliday)

Mark Rylance is Spielberg’s most recent archetype and he’s used the actor as a representation of the grace of old age, the outsider and maybe even an avatar for himself. Two of Rylance’s characters are storytellers, albeit of different kinds. The BFG is a benevolent and selfless storyteller, blowing dreams through children’s windows and enriching their imaginations. Halliday is altogether darker. He created his story (the virtual reality world of The Oasis) to protect himself from the real world and has subsequently created a nightmarish labyrinth. His appearance at the film’s end is tragic, with Spielberg positioning him as a lost soul who never got “a decent meal”.

Both are also outsiders, but it’s in Bridge of Spies’ Rudolf Abel that Spielberg explores this side of Rylance’s screen persona in the most detail. Almost everyone in Bridge of Spies calls for Abel’s head and Spielberg never shies away from showing that he is indeed guilty of the crimes he’s accused of committing. But he’s keen to show Abel’s human side as well. A painter and pragmatist, Abel’s no comic book secret agent, just a regular man doing his national duty, as Donovan’s doing his. The men strike up an unexpected friendship, and we the audience bond with him too. The grace and wisdom Abel represents has extended beyond the man himself.

Spielberg’s thematic range is often reduced to just a handful of things (everymen, wonder, daddy issues), but these are just the tip of the iceberg. Dig deeper, and there’s richness and complexity that goes unnoticed.

Baz and Steve

I love unearthing old interviews with Spielberg. It’s fascinating, and pretty exciting, to look back on things he’s said in the past and see how opinions, approaches, and projects have changed. It’s even better when the interviews I find are lengthy and thoughtful, as this one with legendary UK critic Barry Norman is.

The chat was broadcast prior to the UK release of Always in March 1990 and took place at Amblin’s offices, so not only do you get to hear Spielberg’s thoughts at the start of one of his most transformative decades, but you also get a little tour of his HQ. Look out for the bit with the wishing well and its famous occupant.

Visit the website or hit the subscribe button for more Spielberg goodness.