Ride Away: Spielberg, War of the Worlds and the End of an America Era

In his 2005 take on War of the Worlds, Steven Spielberg takes inspiration from John Ford and The Searchers to portray the end of an American era and the fading of a breed of American hero.

It’s one of the darkest moments in Steven Spielberg’s career. Having narrowly avoided death at the hands (or, rather, laser beams) of a newly-surfaced Martian tripod, suburban father Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise) returns home to his kids, understandably shaken. Staringly wildly into the distance and unable to articulate what he’s just experienced, Ray is also covered in a layer of dust that he seems oblivious to. Dodging questions he eventually makes his way into the bathroom, looks at himself in the mirror and finally grasps the reality of the situation. The dust is not brick and mortar but flesh and bone, the remnants of friends and neighbours who have been vaporised by the Tripod and whose remains have found their way to Ray’s hair, his face, his clothes. The horror hits Ray and he frantically cleans the dust away.

Moments like this inspired many critics to analyse War of the Worlds through the lens of 9/11 when it was released in the summer of 2005, and such comparisons are indeed valid. One of Spielberg’s most anxious and upsetting mainstream films, it actively draws parallels between the carnage unleashed by the invading Tripods and the events of that day with scenes of mass panic, downed aeroplanes and destruction captured through amateur footage. If there was any doubt, Spielberg and screenwriter David Koepp have Ray’s daughter Rachel (Dakota Fanning) ask her father if the invaders are terrorists in a moment that narrowly escapes cliche thanks to Fanning’s panicked, believable delivery.

But the 9/11 angle only scratches the surface of Spielberg’s thematic intentions. Beyond terrorist trauma, Spielberg uses H.G. Welles’ famous novel to tap into ideas that have been key to his career from the very start: power and control, and specifically how those things are wielded by men. Most Spielberg characters are defined by these concepts. Whether it’s David Mann or Chief Brody gaining power over their tormentors in Duel (1971) and Jaws (1975) or Indiana Jones and Alan Grant rejecting it in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Jurassic Park (1993), Spielberg routinely crafts stories around the triumph, anxiety and moral uncertainty caused when control influences people.

War of the Worlds is no different. Indeed, it may even be Spielberg’s defining statement on the subject: an almost entirely hopeless assessment of power filtered through nationality, history and gender. In it, he explores what happens when power is taken away from the powerful and the importance of not turning away from that powerlessness, but rather embracing it. In the film’s often-derided conclusion, Spielberg draws on John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) to underline his overarching point. This is the end of an American era, the death of a form of American masculinity. Whether Ray can evolve into a new era, or whether he will suffer the same fate as Ford’s Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), doomed to drift in a generational no man’s land, is a question Spielberg leaves tantalisingly unanswered.

Ray is a man cut from a familiar Spielbergian mould: the flawed father. This particular father, however, is something different. In Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Richard Dreyfuss’s Roy Neary is as much a child as a parent and Spielberg finds sympathy for him, despite his questionable approach to his kids and abandonment of them at the end of the film. In later movies, Spielberg emphasised the darkness of his father figures (depicting the eponymous hero succumbing to greed in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and Alan Grant possessing an almost violent dislike for kids in Jurassic Park), but like Roy they’re never entirely unlikeable, maintaining enough charm and relatability to hold the audience’s engagement.

Ray, on the other hand, is not likeable at all. In the opening act, his relationship with his children is strained at best, flat-out aggressive at worst. Unaware of the basics of fatherhood, he has no knowledge of Rachel’s favourite TV shows, is ignorant towards her allergies and eating habits, and is utterly lost when she has a panic attack during the Triopods’ first assault. Remarkably, she seems to be the favourite. His bond with son Robbie (Justin Chatwin) has degenerated so much that the boy barely even acknowledges his father’s existence.

But Ray is not just a bad dad; he’s a fundamentally dangerous man who’s more villain than hero. In the movie’s first shot, Spielberg associates him with the Tripods we’ll see later, framing him within the crane he uses in his day job at the dockyard. Spielberg lingers on Ray’s actions, the movement of the machine dominating the soundtrack, its metallic arm taking up the screen. Job done, Ray leaves the crane and is asked by his boss to take an extra shift, a request Ray refuses. The conversation is tense, Ray blocking the request due to “union regulations” (and not, pointedly, any commitment to his children), and it’s framed by Spielberg under the chassis of a passing truck; another nod to the idea that Ray is more machine than man.

The scene shifts to Ray racing through the streets in his car to meet his children and ex-wife Mary-Ann (Miranda Otto), who have – unlike Ray – arrived on time and been waiting half an hour. Ray witheringly complements Mary-Ann’s new partner Tim (David Alan Basche) for his car: “one safe looking vehicle – congratulations”. When the group head into the house, we see an engine sitting on the kitchen table, Ray framed in the background. Throughout his filmography, Spielberg has returned to the kitchen table as a symbol of family in all its love and frustrations. His use of it here is another reminder that machinery defines Ray more than any recognisible humanity.

Already angry at failing to match up to Tim and having been laughed at by Mary-Ann when he asks her to pass his love on to her mother, Ray’s frustration bubbles over in the next scene when he tries to act the father to Robbie. First, he asks about his son’s homework, getting snark in response, and then he suggests a game of catch. The game fails as a bonding session and becomes violently competitive, with Ray hurling the ball at Robbie so hard it smashes a window. Robbie heads back into the house and Spielberg frames Ray, alone in his backyard, within the fractured circle of broken glass he’s created in the window.1 He’s failed to be a good father to Robbie and fails again moments later when Rachel, distressed at seeing her dad retreat to his bedroom for a nap, asks what they’re supposed to eat. “Y’know… order,” comes the response.

By the time he wakes, Ray’s lot has got worse. Robbie has taken his father’s car for a joyride, further undermining the elder Ferrier’s authority, and while Rachel has ordered food, it’s health food, which causes Ray to wretch and verbally scauld his daughter. Every little action that requires nurturing, empathy or subtlety – some level of reasonable parenting – finds Ray wanting, but where he can succeed (or thinks he can succeed) is in action, and Rachel complaining of a splinter in her finger offers him the opportunity to display some of his might.

He beckons her over, keen to remove the splinter and prevent her finger from becoming infected. Rachel, however, demurs. She knows that a lighter touch is necessary and insists that if they just leave the splinter where it is, her body will naturally push it out. It’s not an especially subtle act of foreshadowing from Spielberg and Koepp, but it makes the point: just as Rachel’s body will push out the splinter, so too will the Earth push out the Tripods. Power and control are not within Ray’s grasp with the splinter or the imminent invaders and his attempts to wield them are rendered futile by Spielberg. But that won’t stop him and when the Tripods attack, he’s given the opportunity to prove his worth by protecting the children and returning them to the safety of their mother. It’s a grimly ironic mission, an acknowledgement that only Mary-Ann represents safety. Even as he becomes his children’s protector, Ray’s position as a good father is still ambiguous at best.

Having composed himself after the scene I describe in the opening of this piece, Ray becomes something of an action hero. “We’re leaving this house in 60 seconds,” he tells Robbie and Rachel with the heroic intent of any number of other Cruise characters. He tries to organise the kids, asking them to gather supplies while he goes upstairs to retrieve a small hand gun; a moment that seems darkly funny given the immensity of what Ray and the rest of humanity are up against. Does he really expect a simple firearm to match up to the Tripods’ arsenal, Spielberg asks, not for the last time in the film. A clever cut takes us from the gun, now holstered in the back of Ray’s jeans, to Rachel’s suitcase, decorated with pinks and flowers and now being held by Ray as he rushes his kids to the car. It’s a neat way to capture the dichotomy that will dominate Ray for the rest of the film: the family man and the action hero.

Another key weapon in Ray’s war (and one that’s rendered equally useless by Spielberg later in the film) is the car he commandeers from a friend’s garage. Earlier, we see Ray offering advice on how to fix the vehicle, advice now confirmed to have been correct: again, Ray knows nothing about fatherhood, but he’s in his element with machines. As Ray circles the car, Spielberg shoots the moment from inside, framing Ray within the glass and metal of the vehicle, just as he had been in the crane earlier. He and the kids get in, while the mechanic insists he gets out: the car needs to be returned to its owner later. “Get in Manny, or you’re going to die,” Ray says, a line that recalls the “Come with me if you want to live,” of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator. Terribly, he’s proven right, again: Ray slams the door, speeds off and in seconds Manny is turned to dust by a laser beam.

What comes next is one of Spielberg’s few concessions to blockbuster cliché. John Williams’ propulsive music plays on the soundtrack as we remain in the car with Ray and the kids. A few glimpses into rear view mirrors show further destruction as a Tripod edges nearer. Finally, we move out of the car, looking at it as it rages forward while behind it a bridge is destroyed, sending cars and tankers flying into Ray’s home and those of his neighbours. Fire engulfs the shot before Ray heads into a freeway littered with abandoned cars and terrified people. In a stunning long take, Spielberg’s camera circles the car as Ray, Rachel and Robbie discuss what’s just happened. It’s a thrilling moment, and Ray thrives, but his failures as a father are never far behind: Rachel suffers from anxiety and while Robbie knows how to ease her, Ray doesn’t. “What was – what was that thing you did with her, huh?” Later, when Ray’s escaped the chaos to Mary-Ann’s now-abandoned house, he tries to replicate the trick (“Dad, that’s not how it goes”) and then makes his kids peanut butter sandwiches. “I’m allergic to peanut butter,” says Rachel.

All is quiet at Mary-Ann’s house, but Ray ushers his kids down into the basement for additional protection. It proves to be a wise decision as, during the night, the trio is awoken by a cacophony of explosions, which are later revealed to have been caused by a downed aeroplane. Even here though, Spielberg can’t resist underpinning Ray’s flaws. He and the kids only survive the crash – which tears through the family home – because Robbie knows the house better and bundles his father and sister into a sub-basement, helping them narrowly avoid a fireball. All Ray can do – all he can ever do – is rely on old-fashioned hallmarks of strength, here symbolised by the gun he took before leaving his home, and which he risks his life to keep hold before jumping into the sub-basement. The next morning, Ray emerges into the basement – now wrecked – and out onto the street, where the crashed plane now sits. Panning across the wreckage, Spielberg delivers another neat play on blockbuster convention: an expensive special effect delivered not for spectacle but sadness.2

As the film moves into its second act, Spielberg breaks the fourth wall as a way to announce Ray’s firmer determination. “Look at me,” he says against a black screen before Spielberg cuts to Rachel, looking up at her father by looking through to us in the audience. The reverse shot follows, with Ray looking down at Rachel, Spielberg again breaking the fourth wall as father tells daughter not to look around so she won’t see the plane. Ray’s becoming a better father: kind, decent, sensitive to his children’s needs. It’s a far cry from the man we saw at the start of the film and, in many ways, the Spielbergian ideal of good fatherhood. The problem is, he’s evolving in the wrong film, a film that won’t reward such evolution. Ray and the kids drive away, using the turnpike so it’s quiet and nobody notices the car (now a valuable commodity). Rachel asks to go to the bathroom and Ray lets her, but not before telling her to “go where I can see you”. Ray’s still not earned the kids’ trust though and they ignore him, leaving him only with empty, jokey threats to reassert control: “Every time you guys don’t listen to me, I’m telling your mother, alright. I’m making a list…”

Again, Ray is proven somewhat correct in the following scenes, although it’s a pyrrhic victory. Spielberg follows Rachel as she finds a private area. She comes across a river, which Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski shoot with an air of fairy tale beauty: light shimmering across the water, dandelion fuzz blowing in the breeze. A gentle, lullaby-like tune plays on the soundtrack as Spielberg cuts to a wide shot and a dead body floats by. Spielberg cuts to Rachel as she watches the body. It’s a shot reminiscent of the fourth-wall breaker we saw moments earlier, only here Spielberg and Kaminski increase the sense of horror by having the light reflected from the river play upon Rachel’s face. Williams’s score employs strained violins and Spielberg cuts to another wide as more bodies follow. Rachel starts to panic before Ray arrives, desperately covering her eyes. “I told you to stay where I could see you,” he says, as if that will somehow keep her safe. Ray’s tragic irony is that he’s trying to be a good father in a world where being a good father is almost impossible and any victories that can be found are no guarantee of safety.

The trio’s journey continues and takes them into a crowd of people who want to steal the car and quickly turn nasty. With Spielberg shooting from within the vehicle, the sequence comes to resemble the T-Rex attack in Jurassic Park, with the angry mob thumping against rain-lashed windows in an attempt to get in. Ray’s earlier theft of the vehicle is being repeated, albeit with the roles reversed, as Spielberg again positions his hero’s noble attempts at protection as futile. Accelerating to escape and swerving to avoid a woman and her baby, Ray crashes the car into a telephone pole and the mob smash the windows (one clawing at the glass like one of The Lost World’s Raptors). Ray fires his gun, ironically not to defeat the Tripods but to defend himself and his children from other humans, and buys himself enough time to retrieve Robbie and Rachel.

As he does, another man steals the car at gunpoint, causing Ray to drop his own weapon. He and the kids retreat into the relative safety of a diner, and yet another man picks the gun up and uses it to kill the car thief. Just as the car was an act of futility that almost led to more danger than it was worth, so too is the gun. We see the killing, like the trio, through the window of the diner as Rachel seeks comfort in her brother’s arms, not her father’s. Closing a trilogy of shots based around Rachel’s eyes, we see her in medium close-up crying, looking towards her father. Defeated, unsure of what to do next, and seeing his every attempt at being a good father fail, he covers his face and also descends into tears before looking to his children. There’s no turning away from this, no closing your eyes. Ray, despite his best efforts, cannot protect his kids.

This point is brought into literal reality as the film approaches the end of the second act. Frustrated at the destruction around him, Robbie was earlier demanding to join the army and “get back” at the Tripods. It’s a gesture as futile as Ray taking the gun: what can one man do against these gigantic machines? How exactly can anyone “get back” at them? Ray talks the boy down and Rachel’s insistence that there’d be nobody around to look out for her if Robbie left (another dig at Ray) convinces him to stay. However, as the film moves to a set piece aboard a ferry, Robbie begins to show more leadership. With Tripods emerging, the ferry has to depart and leaves dozens of potential passengers behind, cannon fodder for the invaders. Carrying Rachel, Ray is unable to help but Robbie takes charge, jumping onto the barrier and helping those who’ve been lucky enough to cling to the boat get aboard. A surprised Ray looks on with respect; Robbie’s proven himself mature enough to take life-or-death decisions on his own.

Ray still tries to keep the unit together though. As the trio and their fellow refugees wander the landscape they come across another battle; this time the army is striking back with tanks and planes. Robbie’s pace quickens and eventually he runs towards the battle, despite the protestations of both his father and sister. He wants to fight and when Ray eventually catches up with him, the two argue, Ray begging his son to turn around. Spielberg gives Robbie a medium close-up similar to those Rachel had earlier. It’s a quasi-Spielberg Face, looking off into an unknown distance. But there’s no hope and wonder here; rather fear and an acknowledgement of something terrible over the horizon. “I need to see this; please let me go,” Robbie pleads to his father. It’s an inversion of the plane scene earlier, and with Rachel in trouble a few meters away Ray eventually lets his grip on his son loosen. Robbie does need to see this. He does need to strike out on his own, and there’s nothing Ray can do to protect him, no matter how hard he tries.

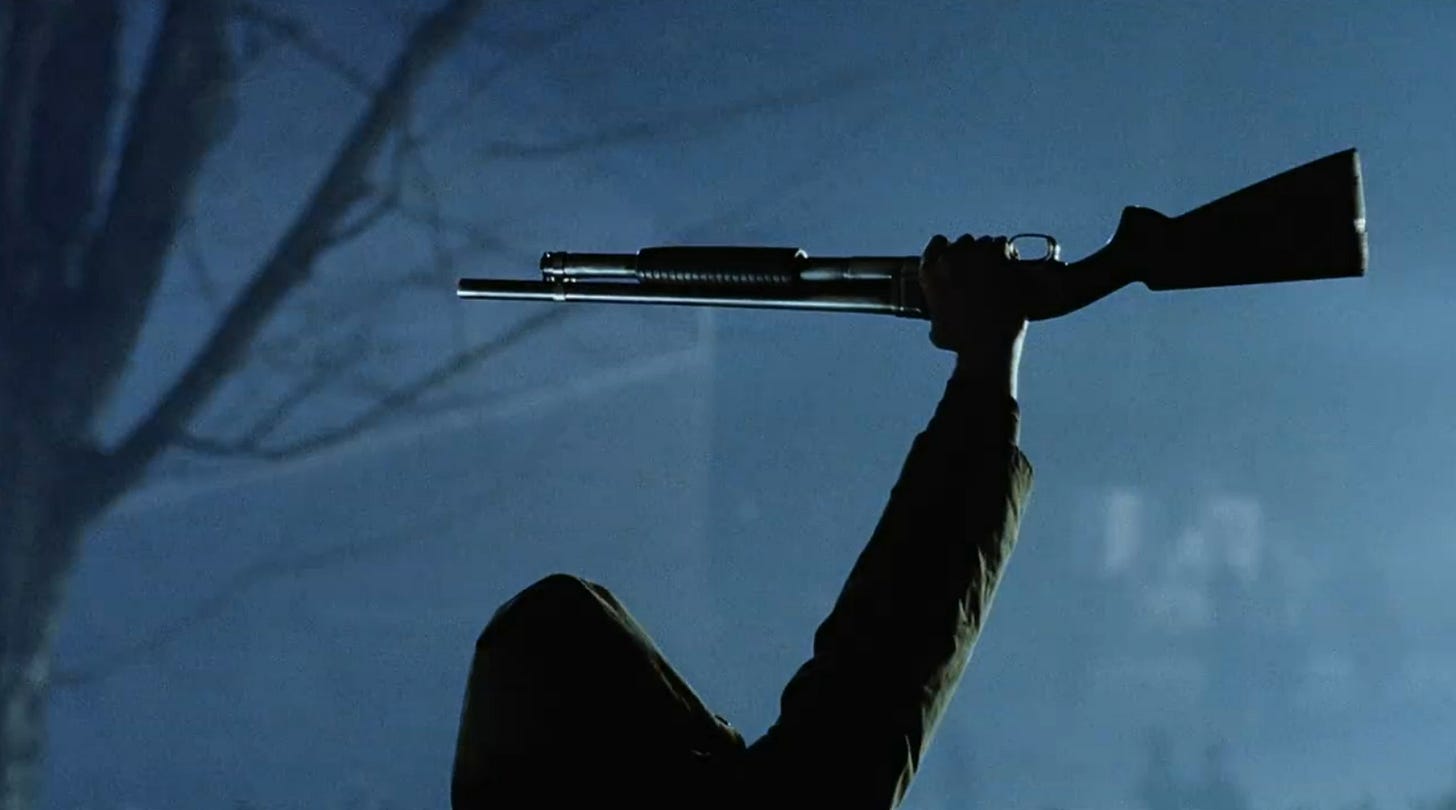

A fireball engulfs the landscape as three Tripods emerge over the horizon. All Ray and Rachel can do is flee, but to where? A form of salvation comes as Spielberg indulges in a bit of pitch-black comedy in the form of a cut taking us from the immensity of the Tripods to a man, clad in a hoody, holding a shotgun over his head – again, as if the gun will be useful. This is Harlan Ogilvy (Tim Robbins), a survivalist who has hunkered down in his basement and so far escaped the wrath of the Tripods. He initially seems like he may be helpful to Ray, but he’s lost his entire family and is wild-eyed and addled by his experiences. He’s openly pessimistic (“Think about it… they defeated the greatest power in the world in a couple of days… walked right over us”) and sees the invasion as more of an extermination than a war. Yet he clings to a grim hope, telling Ray that as a former ambulance driver he knows it’s the ones who “keep their eyes open, keep looking at you, keep thinking” who stay alive. “Running… that’s what’ll kill you and I’m dead set on livin’.”

Ogilvy is another Spielberg standard. He’s the “shadowy reflection” of Ray, the vision of everything Ray could have been, and would have been, had the invasion not brought out a more protective streak: alone, selfish and interested in nothing but his own survival. And he becomes as big a threat to Ray and Rachel as the Tripods themselves, eventually revealing to Ray that his plan is to team up with him and “fight [them] together”. He gets his big chance when a mechanical eye from one of the machines snakes its way into the basement to scope the place out. Knowing that the three of them need to remain silent and out of sight, Ray quietly ushers he and Rachel around the room, nimbly avoiding the machine’s gaze. Ogivly is less subtle. Spying his opportunity, he grabs an axe from the wall and readies himself to bring it down on the eye’s stalk. Ray quietly talks him out of it, but when actual aliens come into the room, Ogilvy arms his shotgun and aims, ready to fire. A wordless tussle breaks out as Ray tries to wrestle the gun from Ogilvy. He ultimately fails, but the aliens are called back to their Tripod before Ogilvy can open fire. The cracks are starting to form and they open wider when the invaders’ harvesting of humans becomes clear. Ogilvy loses his mind, risking drawing the invaders’ attention again, and Ray knows what he needs to do.

Blindfolding his daughter and asking her to sing a lullaby to distract herself, Ray continues to believe he can protect Rachel from the world’s evils. It’s clear that she knows what’s happening though, and even if she isn’t how will Ray explain Ogilvy’s absence? It’s pure desperation and Spielberg compounds Ray’s misery in the next scene when another eye invades (Ray, ironically, taking Ogilvy’s axe to it in defence) and Rachel is taken. In a messy, almost suicidal attack on a Tripod, he’s able to retrieve her, but Spielberg once again renders such noble self-sacrifice all-but useless when the invasion reaches its conclusion. As the reunited father and daughter continue their aimless wander through an increasingly barren landscape, they come across fallen Tripods and it’s revealed that the bacteria natural to the earth has felled them. The invasion is over.

Ray and Rachel’s journey still has one final twist though. With Rachel in his arms, Ray finally returns her to her mother’s home, and it’s revealed that Robbie has survived. He and Ray embrace, Robbie finally addressing Ray as ‘dad’, suggesting a restoration of the family unit. But there’s something amiss. Spielberg’s blocking keeps Ray separate from the rest of the family, the “dad” coming less as a resumption of a previous family order and more like a sign of basic respect.

In this sense, the conclusion resembles the iconic ending of John Ford’s The Searchers, a film and filmmaker Spielberg has spoken glowingly about many times. Indeed, the whole movie is shaped like a restaging of Ford’s classic, with both Ray and Ethan being cast as morally ambiguous heroes in an end-of-an-era landscape. For Ford, that era was the Old West and Ethan’s darkness comes from the racism that’s apparent in his actions throughout. For Spielberg, the era is America’s current frontier and Ray’s darkness comes from his association with the machines and desire for control.

While he’s rehabilitated to a degree (at least in comparison with Ogilvy), Spielberg is careful with the reward he gives his hero. Ray has simply survived and is no more the powerful patriarch than he was at the start of the film. For all his determination to keep his son by his side, for all his (and our) assumption that the fireball killed him, Robbie’s proven himself independent and capable. Ultimately, he doesn’t need his father, at least not in the way Ray believes he does. The respect is there, the acknowledgement of their relationship is there, but there remains no hope of the family unit being restored. There is no hug between Ray and Mary-Ann, no connection between Ray and his former in-laws, no need for Ray to be a protector. Instead, the film simply ends and Ray remains half-way down the street, his position like Ethan’s: distant, frozen in time.

A door has closed on an America era. An era has ended for an American hero. All that’s left is an uncertain future.

Spielberg returns to this imagery twice more in War of the Worlds. The second instance is during the attack on Ray’s car, when a woman and child are framed within a circular hole in the front window. The third instance comes when Ray can only watch on helpless through a circular hole in another car’s front window as Rachel is taken by a Tripod. All three shots act as representations of the human eye, a reference to the sight symbolism Spielberg engages with throughout.

A similar note is struck later in the film where a flaming train speeds past Ray and the kids. This moment arguably has additional resonance because of the significance of the train-wreck in The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) to Spielberg’s formative movie-making.